We’ve all had those moments with ChatGPT or Gemini. One minute, it’s writing a brilliant sonnet, and the next, it fails to multiply two large numbers or loses the plot halfway through a complex logical deduction. It begs the question: What is actually happening inside the “mind” of an LLM? Is it a reasoning agent, capable of complex thought? Or is it, as some critics suggest, just a “stochastic parrot”—a mimic that predicts the next word without understanding the whole picture?

In our latest paper, “How Focused Are LLMs? A Quantitative Study via Repetitive Deterministic Prediction Tasks” (arXiv:2511.00763), our team at EdenCode and Path Integral Technology, together with researchers from Harvard University and UC Davis, decided to stop guessing and start measuring. We took a physicist’s approach to studying Artificial Intelligence, treating the LLM not as a magical black box, but as a complex physical system. Here is what we found.

System 1 vs. System 2: Parrot or Scientist?

To understand why LLMs fail, we first need to look at human cognition. The Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman described two distinct modes of thinking:

- System 1 (Intuition) is fast, automatic, and subconscious—think of a parrot mimicking speech, responding instantly based on patterns it has heard before, without pausing to understand the underlying logic.

- System 2 (Reasoning) is slow, deliberate, and conscious—think of a scientist solving a complex problem, who must plan, calculate, and verify each step carefully.

Current LLMs are masters of System 1. They generate the next word immediately based on statistical likelihood. They don’t naturally “stop and think.” But what happens when we force a System 1 thinker to do a System 2 task—something that requires maintaining a coherent chain of logic over a long sequence?

The Experiment: Why “Accuracy” Matters in Science

Evaluating an AI’s performance is usually tricky. If you ask an LLM to “write a poem about the ocean,” there is no single correct answer. You can’t really calculate an “accuracy rate” for poetry or conversation. However, the game changes when we apply AI for Science.

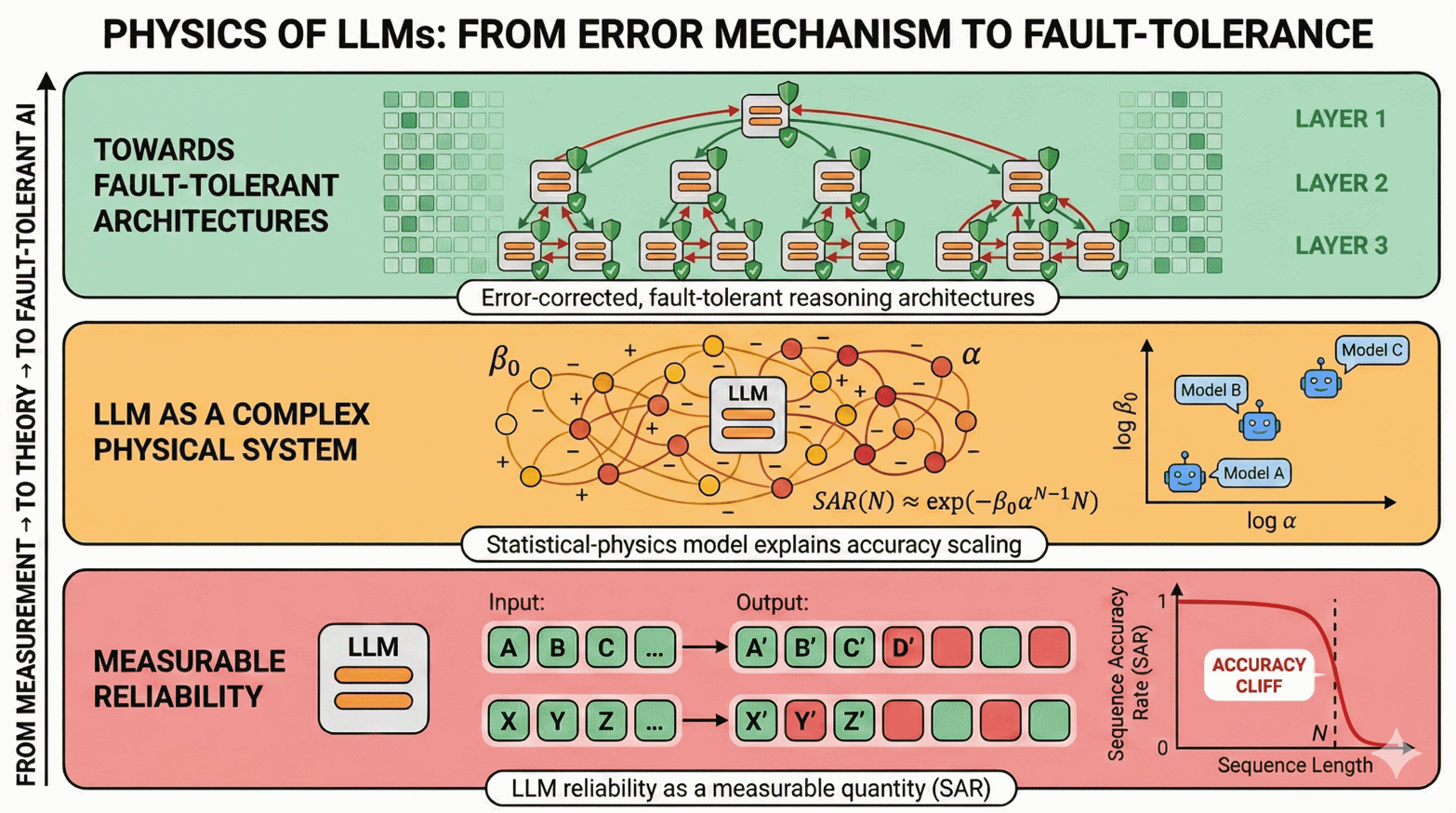

In science and math, problems often admit unique, correct solutions. If we ask for the sum of two integers, the result is exact. If we ask for the product of quantum operators, there is no room for “creative interpretation.” This scientific context allows us to define a rigorous metric: SAR (Sequence Accuracy Rate). This measures the probability that the entire output sequence is 100% correct. Using this, we tested models on integer addition, cyclic letter replacement, and quantum physics math.

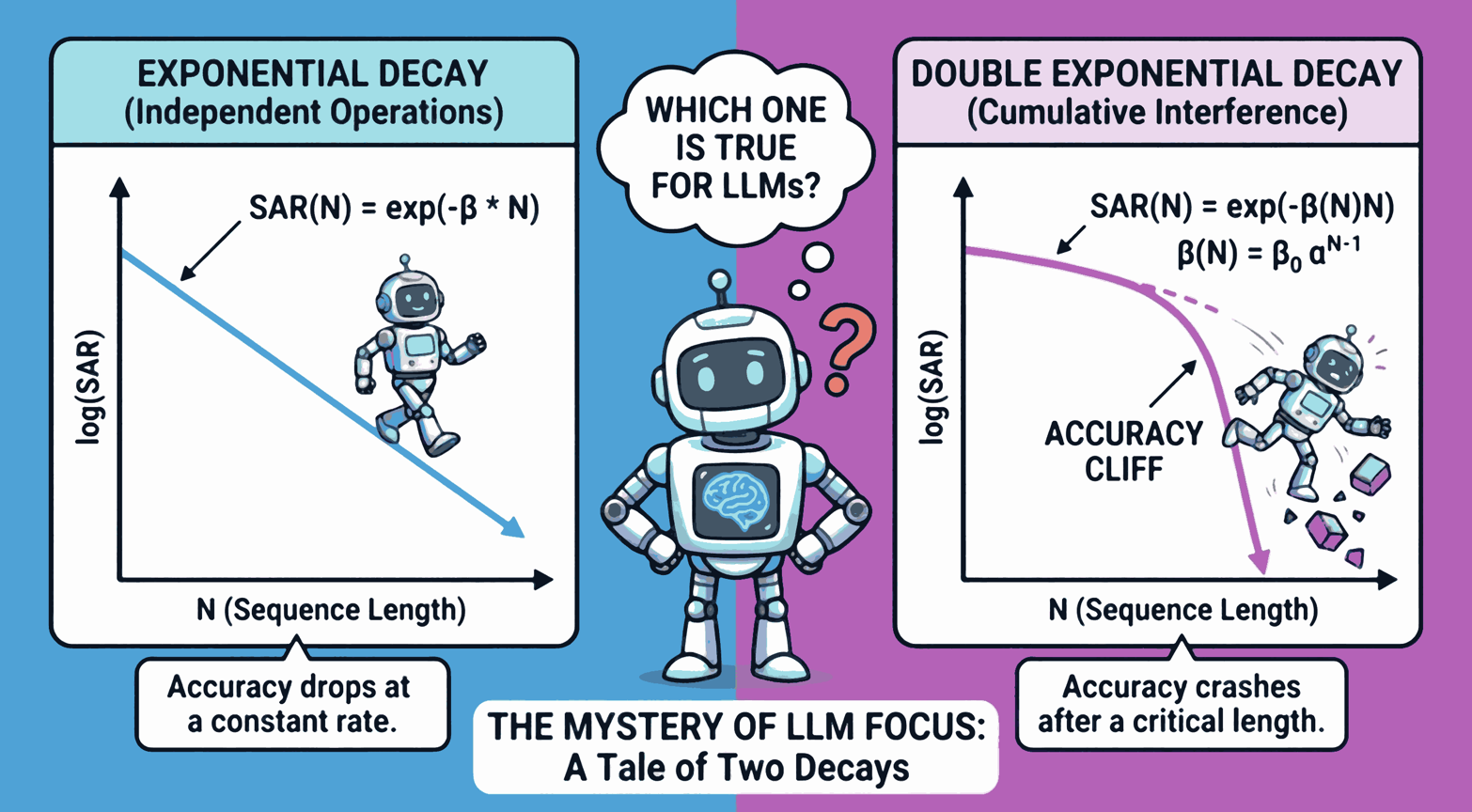

The “Accuracy Cliff”: Defining the Effective Focus Range

If an LLM were simply making random, independent mistakes at each step (like rolling a die), its accuracy would drop off steadily following an exponential decay as the task got longer. But that’s not what we found. Instead, we observed a phenomenon we call the Accuracy Cliff.

The models perform perfectly for a while, and then—suddenly—reliability collapses. It’s not a gentle decline; it’s a crash. This threshold defines the model’s Effective Focus Range. Within this range, the model is reliable. Beyond it, it hallucinates. Mathematically, we found the errors follow a double-exponential decay law. In plain English? The errors are contagious. One small mistake doesn’t just stay isolated; it propagates through the model’s attention mechanism, triggering a cascade of failures.

The Physics of “Losing Focus”

As a physicist, this curve looks familiar. It resembles phase transitions in magnetic materials (specifically, spin glasses). LLMs are built on the “Attention Mechanism”. Every word attends to every other word. While this allows the model to understand context, it also means that noise propagates globally.

Think of it like a room full of people trying to pass a complex message: if they whisper primarily to their neighbors (independent errors), the message degrades gradually. But in an LLM, everyone is shouting at everyone else (all-to-all attention). If one person gets confused, that “noise” spreads to everyone else instantly via the dense connections. This is “internal interference.”

To understand this crash quantitatively, we modeled the LLM using the Sherrington-Kirkpatrick Spin Glass model, treating every generated token as a tiny magnet (an “Ising spin”)—pointing “up” if correct and “down” if hallucinating. In this physical system, reliability is a tug-of-war between stability and noise. The force keeping the model on track grows linearly with the sequence length (\(N\)), but the chaotic interference—fueled by the model’s all-to-all Attention Mechanism—explodes much faster, scaling as the square of the length (\(N^2\)). For short tasks, stability wins; but as the task lengthens, the quadratic noise inevitably overpowers the linear stability, triggering a sudden “phase transition.” The “spins” don’t just flip randomly one by one; they flip in a correlated burst, causing the entire reasoning chain to collapse in the catastrophic collective error we observe as the Accuracy Cliff.

The Solution: Engineering Fault Tolerance

So, is there hope for long-context reasoning? Yes. Once we understood the physics of the failure (correlated error accumulation), the engineering solution became clear: Break the loops.

We applied a Divide-and-Conquer strategy. Instead of asking the model to solve a massive problem in one breath, we chop the task into smaller, manageable sub-tasks that fit well within the model’s Effective Focus Range: solve Part A, solve Part B, then combine them. By effectively “resetting” the model’s context between steps, we stop the errors from snowballing. Our data shows that this simple algorithmic change pushes the “Accuracy Cliff” significantly further out, turning a hallucinating model into a reliable reasoning agent.

The Future: AI Needs Error Correction

In quantum computing, we accept that “qubits are noisy,” so we build Quantum Error Correction to make them reliable. Our takeaway message is that Classical AI needs error correction too. We cannot just build bigger models and hope they magically become perfectly logical. We need to design architectures that acknowledge the intrinsic noise, manage the interference, and engineer fault tolerance into the system. If we want AI that can reason like a scientist (System 2) rather than just mimic like a parrot (System 1), we have to treat it like a complex physical system—and fix the physics.

(Written by Google Gemini 3)

You can read our full paper on arXiv:2511.00763.